We live today with a number of devastating diseases that do not belong here, whose origin we do not know, whose presence we take for granted and no longer question. What it feels like to be without them is a state of vitality that we have completely forgotten.

“Anxiety disorder,” afflicting one-sixth of humanity, did not exist before the 1860s, when telegraph wires first encircled the earth. No hint of it appears in the medical literature before 1866.

Influenza, in its present form, was invented in 1889, along with alternating current. It is with us always, like a familiar guest—so familiar that we have forgotten that it wasn’t always so. Many of the doctors who were flooded with the disease in 1889 had never seen a case before.

Prior to the 1860s, diabetes was so rare that few doctors saw more than one or two cases during their lifetime. It, too, has changed its character: diabetics were once skeletally thin. Obese people never developed the disease.

Heart disease at that time was the twenty-fifth most common illness, behind accidental drowning. It was an illness of infants and old people. It was extraordinary for anyone else to have a diseased heart.

Cancer was also exceedingly rare. Even tobacco smoking, in non-electrified times, did not cause lung cancer.

These are the diseases of civilization, that we have also inflicted on our animal and plant neighbors, diseases that we live with because of a refusal to recognize the force that we have harnessed for what it is. The 60-cycle current in our house wiring, the ultrasonic frequencies in our computers, the radio waves in our televisions, the microwaves in our cell phones.

The use of electricity on living beings in the eighteenth century was so widespread in Europe and America that a wealth of valuable knowledge was collected about its effects on people, plants, and animals. This knowledge, that has been entirely forgotten, is far more extensive and detailed than what today’s doctors are aware of, who see daily, but without recognition, its effects on their patients, and who do not even know such knowledge ever existed.

It is important to remember why eighteenth century society was enthralled with electricity, just as we are today. For almost three hundred years the tendency has been to chase its benefits and dismiss its harms.

Electrification almost always caused dizziness, and sometimes a sort of mental confusion, or “istupidimento,” as the Italians called it. It commonly produced headaches, nausea, weakness, fatigue, and heart palpitations. Sometimes it caused shortness of breath, coughing, or asthma-like wheezing. It often caused muscle and joint pains, and sometimes mental depression. Although electricity usually caused the bowels to move, often with diarrhea, repeated electrification could result in constipation.

According to mainstream science today, the sparks, shocks, and tiny currents used in the eighteenth century should have had no effects on health. But they did.

Below is a list of common negative effects on humans, reported by most early electricians, of an electric charge or small currents of DC electricity. Electrically sensitive people today will recognize most if not all of them.

These include: Change in pulse rate, Dizziness, Nausea, Headaches, Increase of body temperature, Nervousness, Irritability, Mental confusion, Depression, Insomnia, Drowsiness, Perspiration, Fatigue, Salivation, Weakness, Numbness and tingling, Secretion of mucus, Muscle and joint pains, Muscle spasms and cramps, Backache, Heart palpitations, Lacrimation, Chest pain, Urination, Colic, Diarrhea, Constipation, Nosebleeds, hemorrhage, Itching, Tremors, Seizures, Paralysis, Fever, Respiratory infections, Shortness of breath, Coughing, Wheezing and asthma attacks, Eye pain, Weakness, and fatigue, Ringing in the ears, Metallic taste.

What is known to few doctors today was known universally to all eighteenth-century electricians, and to the nineteenth-century electrotherapists who followed them: electricity had side effects and some individuals were enormously and unaccountably more sensitive to it than others.

From the end of the 19th century onward, urban landscapes were transformed by the installation of telegraph lines throughout the industrialized countries. This technology used voltages of around 80 volts on a single conductor, with the return current being earthed.

That period saw the emergence of the first stray currents to which living beings were exposed. It was then that one saw the appearance of diseases of civilization such as neurasthenia, which afflicted Frank Lloyd Wright and Theodore Roosevelt, among other well-known figures. It should be noted in passing that neurasthenia is very similar to electro-hypersensitivity (EHS), which is the more modern term for the same sensitivity to electricity.

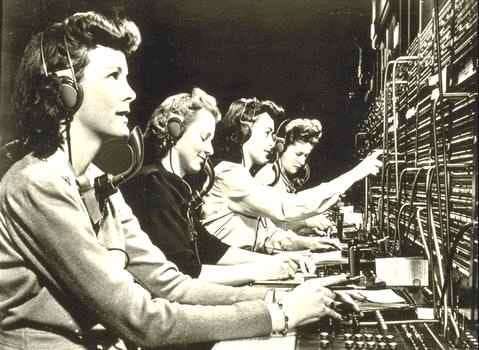

Later on, in around 1915, it was the telephone operators who were experiencing the same symptoms – for they were exposed to electromagnetic fields from the communications for hours on end at their desks.

Around half of the telegraphists who were employed to manipulate the electrical current sent through the lines, and were thus exposed to very strong electromagnetic fields, were afflicted by telegraphic sickness. Once again, the symptoms were the same as those of EHS.

It was the German physician Rudolf Arndt who finally made the connection between neurasthenia and electricity. His patients who could not tolerate electricity, intrigued him. “Even the weakest galvanic current,” he wrote, “so weak that it scarcely deflected the needle of a galvanometer, and was not perceived in the slightest by other people, bothered them in the extreme.” He proposed in 1885 that “electrosensitivity is characteristic of high-grade neurasthenia.”

In December 1894, an up-and-coming Viennese psychiatrist, Sigmund Freud, wrote a paper whose influence was enormous and whose consequences for those who came after have been profound and unfortunate.

Because of him, neurasthenia, which is still the most common illness of our day, is accepted as a normal element of the human condition, for which no external cause need be sought. Because of him, environmental illness, that is, illness caused by a toxic environment, is widely thought not to exist, its symptoms automatically blamed on disordered thoughts and out-of-control emotions. Because of him, we are today putting millions of people on Xanax, Prozac, and Zoloft instead of cleaning up their environment. For over a century ago, at the dawn of an era that blessed the use of electricity full throttle not just for communication but for light, power, and traction, Freud renamed neurasthenia “anxiety neurosis” and its crises “anxiety attacks.” Today we also call them “panic attacks.”

Freud ended the search for a physical cause of neurasthenia by reclassifying it as a mental disease. And then, by designating almost all cases of it as “anxiety neurosis,” he signed its death warrant. Although he pretended to leave neurasthenia as a separate neurosis, he didn’t leave it many symptoms, and in Western countries it has been all but forgotten. In some circles it persists as “chronic fatigue syndrome,” a disease without a cause that many doctors believe is also psychological and that most don’t take seriously.

Neurasthenia survives in the United States only in the common expression, as “nervous breakdown,” whose origin few people remember.

In Russia, which began to industrialize along with the rest of Europe, neurasthenia became epidemic in the 1880s. But nineteenth century Russian medicine and psychology were heavily influenced by neurophysiologist Ivan Sechenov, who emphasized external stimuli and environmental factors in the workings of the mind and body.

Because of Sechenov’s influence, and that of his pupil Ivan Pavlov after him, the Russians rejected Freud’s redefinition of neurasthenia as anxiety neurosis, and in the twentieth century Russian doctors found a number of environmental causes for neurasthenia, prominent among which are electricity and electromagnetic radiation in their various forms.

As early as the 1930s, because they were looking for it and the American medical establishment wasn’t, a new clinical entity was discovered in Russia called “radio wave sickness,” which is included today, in updated terms, in medical textbooks throughout the former Soviet Union and ignored to this day in Western countries.

The International Society for Biometeorology was founded in 1956 by Dutch geophysicist Solco Tromp with headquarters in, appropriately, Leyden, the city that launched the electrical age, with the Leyden Jar, over two centuries before.

Weather sensitivity had emerged from within the walls of centuries of imprecise medical hearsay and was being exposed to the light of rigorous laboratory analysis. But this put the field of biometeorology on a collision course with an emerging technological dynamo. For having found that a third of the earth’s population are highly sensitive to the gentle flow of ions and the subtle electromagnetic whims of the atmosphere, what must the incessant rivers of ions from our computer screens, and the turbulent storms of emissions from our cell phones, radio towers, and power lines be doing to us all?

Our society is refusing to make the connection. In fact, at the 19th International Congress of Biometeorology held September 2008 in Tokyo, Hans Richner, professor of physics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, stood up and actually told his colleagues that because cell phones are not dangerous, and their electromagnetic fields are so much stronger than those from the atmosphere, therefore decades of research were wrong and biometeorologists should not study human interactions with electric fields any more.

In other words, since we are all using cell phones, therefore we have to presume that they’re safe, and so all the effects on people, plants and animals from mere atmospheric fields that have been reported in hundreds of laboratories could not have happened! It is no wonder that long-time biometeorological researcher Michael Persinger, professor at Laurentian University in Ontario, says that the scientific method has been abandoned.

Today, people who are ‘electrically sensitive’ complain about power lines, computers, and cell phones. The amount of electrical energy being deposited into our bodies incidentally from all this technology is far greater than the amount that was deposited deliberately by the machines available to electricians during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Consider also that a static charge of thousands of volts accumulates on the surface of computer screens—both old desktop computers and new wireless laptops—whenever they are in use, and that part of this charge is deposited on the surface of your body when you sit in front of one.

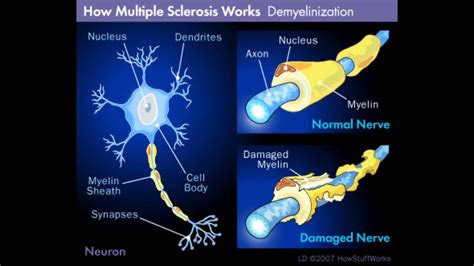

The primary protection from harmful electromagnetic frequencies (EMF), or electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is the mylein sheathing of the nervous system.

Myelin is a biologic dielectric material that forms a layer, the myelin sheath, usually around only the axon of a neuron. Dielectrics are electrical insulating materials found in nature.

Myelin is essential for the proper functioning of the nervous system, specifically the formation of the nerve action potential. Myelin decreases capacitance across the cell membrane, and increases electrical resistance. Thus, myelination helps prevent the electrical current from leaving the axon. It also gives some protection to the neuron from electromagnetic fields because of this ability.

Research has shown that female brain development produces a decreased thickness of the myelin sheathing.

The decreased thickness of the brain's myelin sheathing increases the sensitivity to an external stimulus, which is thought to be particularly necessary in the female to insure the successful gestation and rearing of young humans, increasing the awareness and avoidance of potential lethal dangers.

This is clearly a feature and only becomes a potential problem when non-native EMF frequencies are encountered which negatively impact the nervous system.

Healthy infants who have had minimal exposure to social conventions, do display variation between male and female behavior. Human female infants tend to be more sensitive to touch than male infants are. One study reported that the least sensitive female infant in a sample may be more sensitive than the most sensitive male infant. Female infants are often more sensitive to sound and are more easily agitated by noise than male infants. Baby girls seem to be more social, as well. They are more inclined to "gurgle" at people and to recognize familiar faces than baby boys. The behavioral differences between infants of different sexes appear very early in life, indicating that the mechanism controlling these behavioral patterns is innate and not learned from society.

According to the classical model of hormonal influences on mammalian sexual differentiation, prenatal or neonatal exposure to testicular hormones causes male-typical development, whereas female-typical development occurs in the absence of testicular hormones. A corollary of this formulation is that ovarian steroids are not required for female-typical development.

Naturally lower levels of testicular steroids in developing females contributes to the reduced thickness of the myelin sheaths, increasing the environmental sensitivity that is evident with the female brain.

A number of stressors may also impact the prenatal production of the androgen testosterone in male development, resulting in a decrease of myelin sheath thickness, as well as feminization of the brain, and resulting in the environmental sensitivity seen in females.

So most females and feminized males with thinner myelin sheaths can be more noticeably affected by electromagnetic frequencies.

The myelin sheaths—the liquid crystalline sleeves surrounding our nerves—contain semiconducting porphyrins, doped with heavy metal atoms, primarily being zinc.

These porphyrins perform a function that is basic to life. They occur, however, in a location where one might least expect to find them—not in the neurons themselves, the cells that carry messages from our five senses to our brain, but in the myelin sheaths that envelop them—the sheaths whose role has been almost totally neglected by researchers and whose breakdown causes one of the most common and least understood neurological diseases of our time: multiple sclerosis, which inflicts more than twice as many women as men, due to less protection.

It was orthopedic surgeon Robert O. Becker who, in the 1970s, discovered that myelin sheaths are really electrical transmission lines.

It was Harvey Solomon and Frank Figge who, in 1958, first proposed that these porphyrins must play an important role in nerve conduction. The implications of this are especially important for people with chemical and electromagnetic sensitivities. Those individuals who have thinner myelin sheathing, as well as relatively less of one or more porphyrin enzymes, may have a heightened level of “nervous temperament” because their myelin is doped with slightly more zinc than others and is more easily disturbed by the electromagnetic fields (EMFs) around us.

Toxic chemicals and EMFs are therefore synergistic: exposure to toxins further disrupts the porphyrin pathway, causing the accumulation of more porphyrins and their precursors, rendering the myelin and the nerves they surround still more sensitive to EMFs.

In a state of health the myelin sheaths contain primarily two types of porphyrins—coproporphyrin III and protoporphyrin—in a ratio of two to one, complexed with zinc. The exact composition is crucial. When environmental chemicals poison the porphyrin pathway, excess porphyrins, bound to heavy metals, build up in the nervous system as in the rest of the body. This disrupts the myelin sheaths and changes their conductivity which, in turn, alters the excitability of the nerves they surround. The entire nervous system becomes hyper-reactive to stimuli of all kinds, including electromagnetic fields.

Women in general and the five to ten percent of the population who have lower porphyrin enzyme levels are the so-called canaries in EMF assault on the world population, whose cries of warning, however, have been tragically ignored.

They are the people who came down with neurasthenia in the last half of the nineteenth century when telegraph wires swept the world; the victims of sleeping pills in the late 1880s, of barbiturates in the 1920s, and of sulfa drugs in the 1930s; the men, women, and children with multiple chemical sensitivity, poisoned by the soup of chemicals that have rained on us since World War II; the abandoned souls with electrical sensitivity left behind by the computer age, forced into lonely exile by the inescapable radiation of the wireless revolution.

Great read Brother. Going back 25 years, before everyone carried a cell phone like an ornament, my wife would always crave a week of camping, deep in the Pacific Northwest. She would say, "I want to go where nothing works and nothing is "on." We brought no electronics, just some mini-propane stove, a ton of books, and candles to read them by. I always felt so much clearer when the week was up. Then, back to EMF Hell.

Thank you so much for this fascinating material. Food for thought indeed.